Uvira, a town in South Kivu Province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), continues to reveal a hidden face of deep suffering and danger facing some of its residents, particularly the Banyamulenge community. While the central authorities in Kinshasa keep claiming that security has been restored and that the Banyamulenge remained in the town without any problems, new information and images that have emerged show a very different reality.

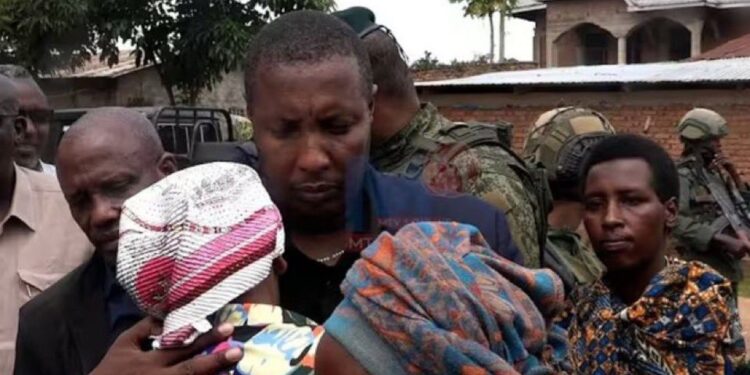

Videos circulating on social media show General Fabien Dunia Kashindi, the commander of the 33rd Military Region, together with his team, searching for the few Banyamulenge who were still hiding in the town of Uvira. In these videos, General Dunia is seen speaking with elderly men and women, among the few who chose not to flee after many others had left the town due to insecurity.

One of the people seen in the videos explains that he and his wife survived only because the local neighborhood (quartier) leader hid them in a very small room resembling a kitchen. He says they spent many days hiding in that room, living in extreme fear of being killed. He adds that their house was attacked by Wazalendo groups, completely looted, and severely damaged.

In the recorded statements, General Dunia promises that these people should be returned to their home, but he also admits that the problem goes beyond his personal authority. He says that a large delegation from Kinshasa is expected in Uvira, led by the Minister of Internal Security, and that his delegation will publicly receive and handle their complaints. For his part, he explains that what he can do is ask the Wazalendo to leave the house, but he gives no firm guarantee regarding the safety of these civilians.

These images and testimonies are strong evidence that contradicts the narrative of the DRC government, which claimed that the Banyamulenge who fled Uvira did so because they were misled or forced by the AFC/M23 coalition. What is clearly shown is that the main reason for fleeing was to save their lives, due to threats, violence, and killings that were looming over them.

Historically, in the Uvira area and neighboring territories such as Fizi, Mwenga, and others, the Banyamulenge have long faced discrimination, ethnic-based conflicts, and repeated acts of violence, as documented by human rights organizations. This adds to the broader context of insecurity in eastern DRC, where armed groups claiming to be community-based militias (Wazalendo) and state security forces have both been accused of involvement in abuses against civilians.

It is clear that the flight of many Banyamulenge was not an act of cowardice or manipulation, but rather a rational decision aimed at preserving their lives. As these testimonies show, remaining in the town meant exposing oneself to grave danger, while some people survived only by hiding, like captives in their own country.

All of this reveals a deeply painful reality Uvira is not a peaceful town as portrayed by the authorities in Kinshasa, but rather a place where a deadly trap still exists for certain civilians. Political statements unsupported by concrete action continue to lose credibility in the eyes of those who have suffered this violence.

This account, based on images and testimonies, calls for an independent and thorough investigation into what happened in Uvira, the implementation of concrete measures to protect all civilians without discrimination, and the restoration of the lost trust between the population and state institutions. Uvira remains a serious test for the DRC government and the international community regarding the protection of life and human rights in the eastern part of the country.